INTRODUCTION

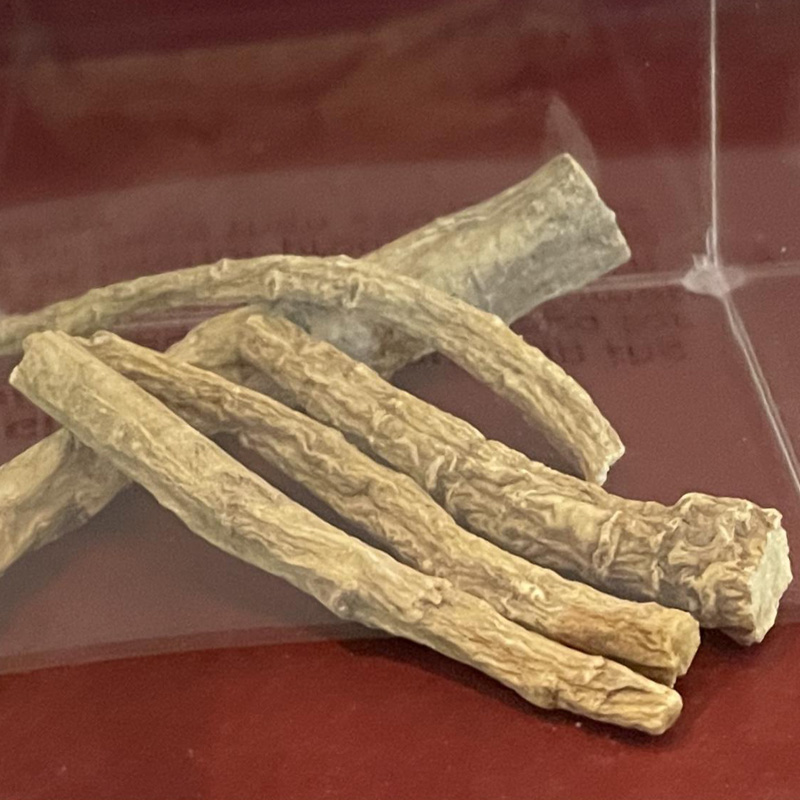

American trade with China began in 1784, when the United States was just entering the world stage. U.S. consumers craved Chinese products such as tea, porcelain, and silk. To meet high demand, merchants traded silver, ginseng, and the highly desired opium.

Eleven members of the Forbes extended family traded in China between 1785 and 1887, profiting from tea and other exports, and from smuggling opium. They developed shipping expertise and devised strategies to evade Chinese officials. Stories, objects, and wealth from the China Trade enriched Forbes family life and the lives of prominent Boston merchant families like the Adamses, Cabots, Coolidges, Lodges, Lowells, Lows, Peabodys and Saltonstalls. These families also used their acquired wealth for expansive philanthropic endeavors from which we still benefit.

The legacy of America’s Chinese opium trade persists today. Its profits built many esteemed institutions. American business practices and sea routes developed from the trade. Perceptions formed by Americans led to Chinese stereotypes and racism that endure and complicate our trade and diplomacy with China. Opium, which irreparably damaged China, continues its destruction in China and the U.S.

MUSEUM STATEMENT

This exhibition is an effort by the Forbes House Museum trustees, staff and guides to confront the complicated history of harm, addiction, and wealth generated by the opium trade, and to explore the roles played and represented by the objects, people, and house we interpret. We acknowledge the painful effects of the opium trade that are still felt by many today. We welcome your input as we explore this facet of the Forbes family history.

PAGE MENU

Topic 1: Global China Trade

Topic 2: Smuggling & Consumption of Opium

Topic 3: Forbes Family Business

Topic 4: Chinese Exports & Forbes Family Wealth

Topic 5: Commissioner Lin ZeXu, the “Century of Humiliation,” and Ethnocentrism in the China Trade

Topic 6: Philanthropy and Lasting Effects of the Opium Trade

Global China Trade

The Trade Route

Voyages from Boston to China in the 1800s were long and often dangerous. Whether traveling east around the Cape of Good Hope in Africa or west around Cape Horn and South America, the round-trip journey took about a year or two, including several months in Guangzhou (Canton) to conduct business. Along trade route stops for products and supplies, Forbes family members encountered vastly different parts of the world. A crucial stop for American traders was in Smyrna, Turkey where they sourced opium en route to China. India was also a significant producer of the drug, but, by this time, the British East India Company had established a monopoly there.

As they sailed around the globe, traders interfaced with many different types of people.

What would that experience have been like for communities on land and for the traders themselves?

Commodities of the China Trade

Sandalwood from Hawaii and other Pacific islands was used for making beautiful, aromatic furniture and decorative items. Used as an herb, it calmed the nerves and soothed the skin. Sandalwood, too, was decimated.

Silk, nankeen cloth and other textiles from China were highly desired in the United States. Nankeen cloth, made in Nankeen, China, was a yellowish cotton cloth used to make clothes.

Porcelain sets and other dishwares from China were highly prized by American consumers. Many of the Boston traders had several sets.

Think about the things you have in your home.

Where did they come from?

How far did they travel?

Smuggling & Consumption of Opium

Smuggling Opium

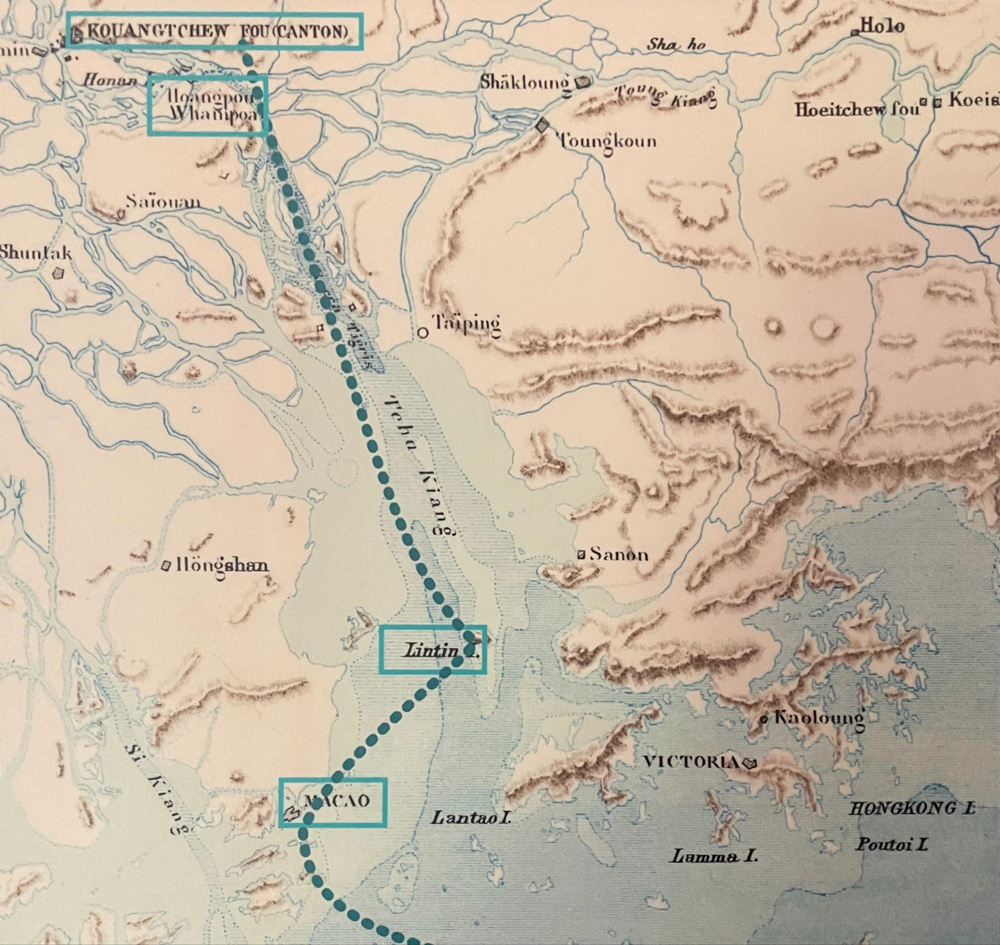

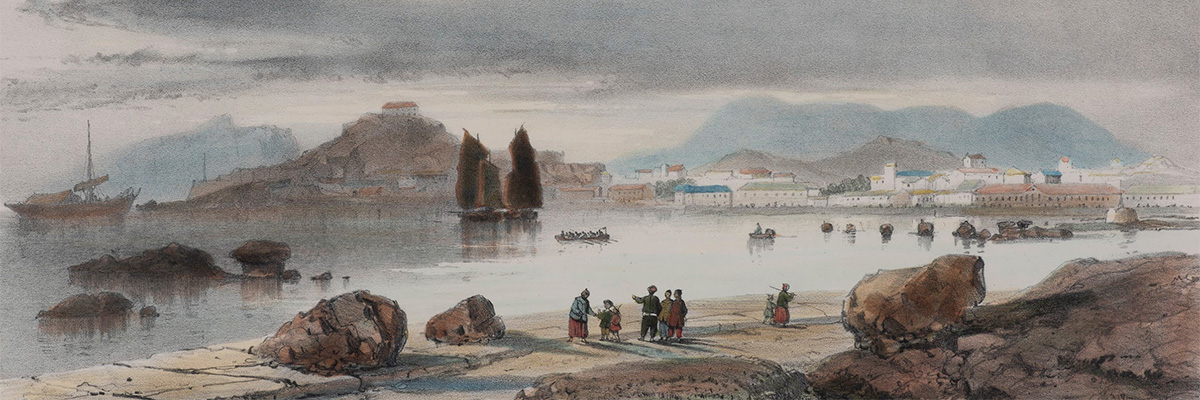

In order to access the trading ports in China, a typical route of one of the Forbeses’ trade voyages would have first taken them to Macau, a Portuguese Colony located across the Pearl River delta from Hong Kong. Next, the ships would have sailed up the Pearl River to Lintin Island and the Bocca Tigris, then up to the Whampoa anchorage. All foreign traders were required to dock and could not go beyond this area.

To transport goods, merchants hired Chinese workers to come and unload the ships, and pay taxes and bribes. Once these needs were met, only then could the ship’s Captain and dignitaries travel further up the river on sampans and other small craft to accompany their goods to Gaungzhou, which was then known as Canton.

Canton was the first trading capital in China. In fact, trading blossomed there 1000 years before Westerners arrived. During the 19th-century China Trade, strict rules regulating trade determined when and how foreign merchants could access the city. This painting depicts some of these restrictions, including the wall that separated the trading area from the city. Western traders could not trade directly with the Chinese as individuals; instead, they interfaced with an association of Chinese merchant officials known as the cohong. Europeans were allowed to live only in this section on the harbor, which came to be called the Thirteen Factories. The painting shows the western-style facades of the buildings in this quarter, and the nationalities represented in these offices.

For what reasons do you think the Chinese government imposed restrictions on trade?

What effect would this have had on interpersonal and international relationships?

Junks are Chinese ships with fully battened sails — rigid but flexible members (battens) slide into the sailcloth, parallel to airflow, to increase the sail’s effectiveness. Small Chinese junks were fast, nimble, and used to transport opium up the Pearl River to Guangzhou (Canton) from Nei Lingding (LinTin) Island, where larger American ships would anchor. Collaboration between American merchants and local Chinese pilots made the China Trade possible.

Consuming Opium

The earliest evidence of opium use can be found in the ancient cultures of Mesopotamia and Egypt. Opium had even been used for thousands of years in China for medicinal purposes with no problems. It was not until smoking was introduced by Westerners, initially in the form of tobacco mixed with opium, that it started to be widely misused, leading to addiction.

By 1838, roughly one-third of the Chinese population was addicted to opium. Opium smuggled by the Forbeses and others fueled this epidemic. Opium addiction has never left China. In the early 20th century, it was estimated that 27% of Chinese males were opium users. In the 1950s, about 5% of the Chinese population was addicted. While accurate statistics are difficult to find, addiction in China is on the rise again. The effects of the opium trade continue to impact the current opioid epidemic.

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, Americans used opium and its derivatives, morphine and heroin, for both pain and pleasure. Laudanum, another substance that was used, consisted of morphine and wine. It was often prescribed for women who had “nervous troubles.” All of these drugs were legally allowed in the U.S. until the Food and Drug Act of 1904.

In the 19th century, opium was typically smoked through a pipe, designs of which varied in material, quality and expense.

Who were the primary suppliers and traders of opium globally in the 19th century?

Who were the primary users?

How might drug use in certain populations relate to the development of stereotypes about these populations?

Forbes Family Business

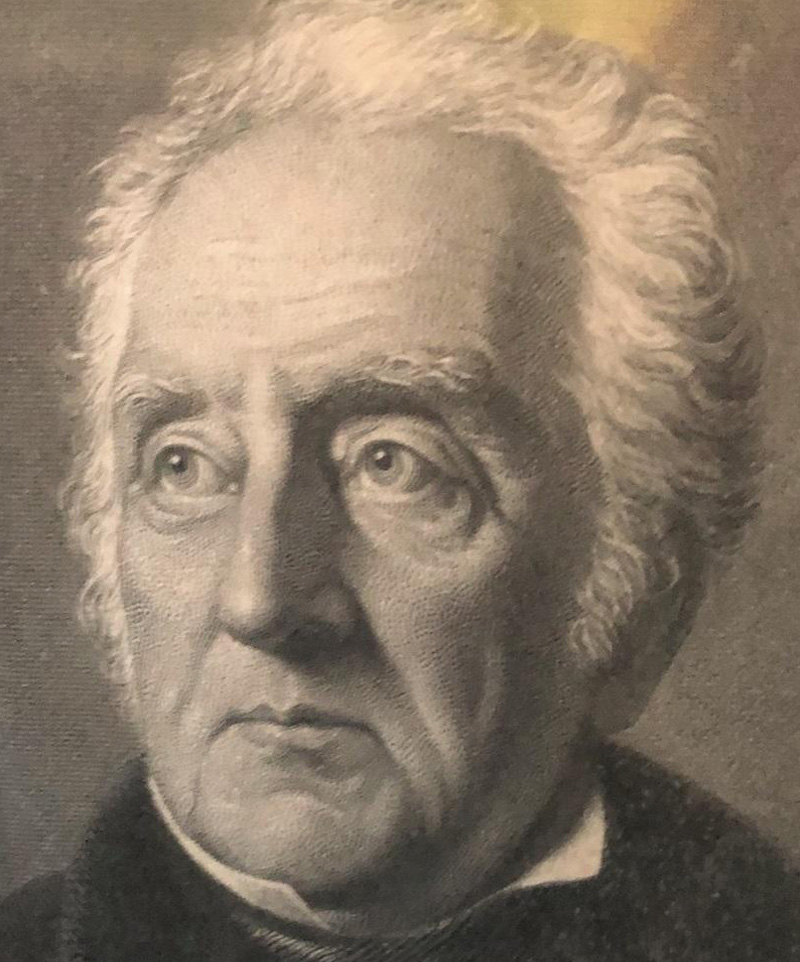

Thomas Handasyd Perkins

(1764–1854)

Thomas Handasyd Perkins recruited many members of the Forbes family to work in his firm and enter the China Trade. Perkins was a prominent Boston merchant in the China Trade and the brother of Margaret Perkins Forbes, for whom the Forbes House was built. Prior to opium, he traded slaves in Haiti and furs from the Pacific Northwest and the South Atlantic Islands. The profits from these businesses enabled him to be a benefactor of the Perkins School for the Blind, the Boston Athenaeum, and Massachusetts General Hospital; he was the moving force behind the Bunker Hill Monument.

John Perkins Cushing

(1787-1862)

John was the first of the Forbes extended family to work in China. After his father’s death, he left Boston at age 16 to clerk in the Perkins counting house for his uncle, T.H. Perkins. Cushing became the sole agent for Perkins & Co. when the main agent died while Cushing was en route to China. He remained in China for 30 years, and initiated the firm’s and family’s relationship with the powerful hong merchant, Hou Qua. In 1828, he drafted a China Trade business plan that included opium as a trade commodity. His success enabled his charity, and at his death, the New York Times wrote that: “He was so noted for liberality to the poor that their pertinacity drove him from Boston, where he once had his residence.”

Thomas Tunno Forbes

(1802-1829)

Thomas, the eldest of the three brothers, sailed for China in 1827, where he was head of Russell & Co. in Guangzhou (Canton), which had merged with Perkins & Co. Thomas died aboard the Yacht Haide in a typhoon off Macao in 1829.

Portrait of Thomas Tunno Forbes

late 19th century

Photographic print

FHM 1965.1.236

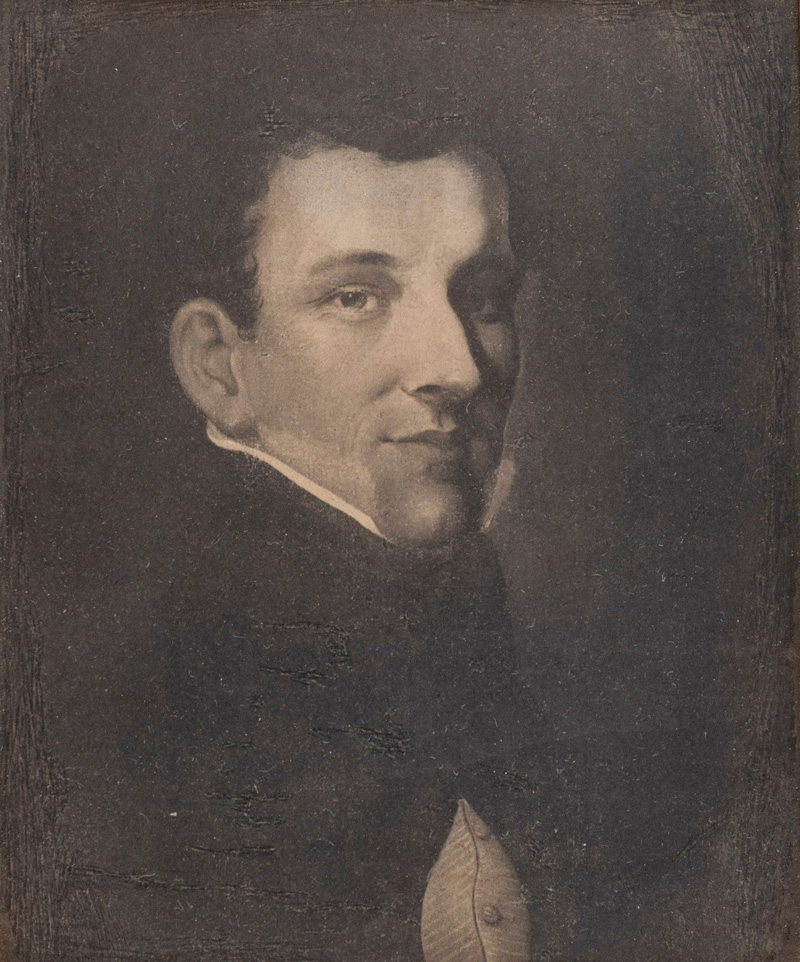

Robert Bennet Forbes

(1804-1889)

Ben was the second son of Margaret Perkins and Ralph Bennet Forbes. He began to work for the family’s shipping company Perkins & Co. when he assisted with a voyage to China at the age of 13. After this first trip, he sailed continuously to and from China, and became a Captain at the age of 21.

Portrait of Robert Bennet Forbes

Lam Qua (Chinese, 1801-1860),

c. 1830-45

Oil on canvas

FHM 1967.1.017

Gift of the Heirs of Allan Forbes

How have ideas about labor, age, and independence shifted over time?

John Murray Forbes

(1813-1898)

John Murray was the third son of Margaret Perkins and Ralph Bennet Forbes. He began to work for the family shipping/trading company at a young age and amassed a great fortune. Unlike his brother, he later invested in a number of businesses within the United States, including propelling the construction of the Michigan Central and Chicago, Burlington, and Quincy railroads during the late-19th century.

John Murray Forbes

Portrait attributed to Lam Qua

Oil on panel

Margaret Perkins Forbes

(1773-1856)

Margaret Perkins was the sister of Thomas Handasyd Perkins and nine other siblings. She married Ralph Bennet Forbes and endured his business failures, while her brother, Thomas, bailed them out. She was the mother of eight children, including the brothers Thomas Tunno, Robert Bennet, and John Murray Forbes. Of her five daughters, four survived into adulthood. One daughter married and the rest remained at home with their mother. In 1833, using monies from Thomas’s estate, Ben and John Murray built the Forbes house for their mother. Margaret Forbes summered here until her death.

Portrait of Margaret Perkins Forbes

Unknown Artist, undated

Chalk and pencil on paper

FHM 1603.000

Rose Greene Smith Forbes

(1802-1885)

Rose Forbes married Ben Forbes in 1834 and moved to Milton. Rose had three children: Robert, Edith, and James. She spent her time entertaining and visiting relatives, and writing to her husband, her son Bob, and other family members who were abroad and in China. She enjoyed planning the décor for her new summer house in Manchester, Massachusetts. In the early years of her marriage, Rose was left alone to raise her young children, while her husband was gone on global journeys for as long as three years at a time.

Portrait of Rose Greene Smith Forbes

Unknown Artist, c. 1900

Oil on canvas

FHM L1966.17.001

Gift of Edith F. Perkins, Alice D. Hooper, and Elsie P. Youngman

How did American traders like the Forbeses rationalize their involvement in the opium trade?

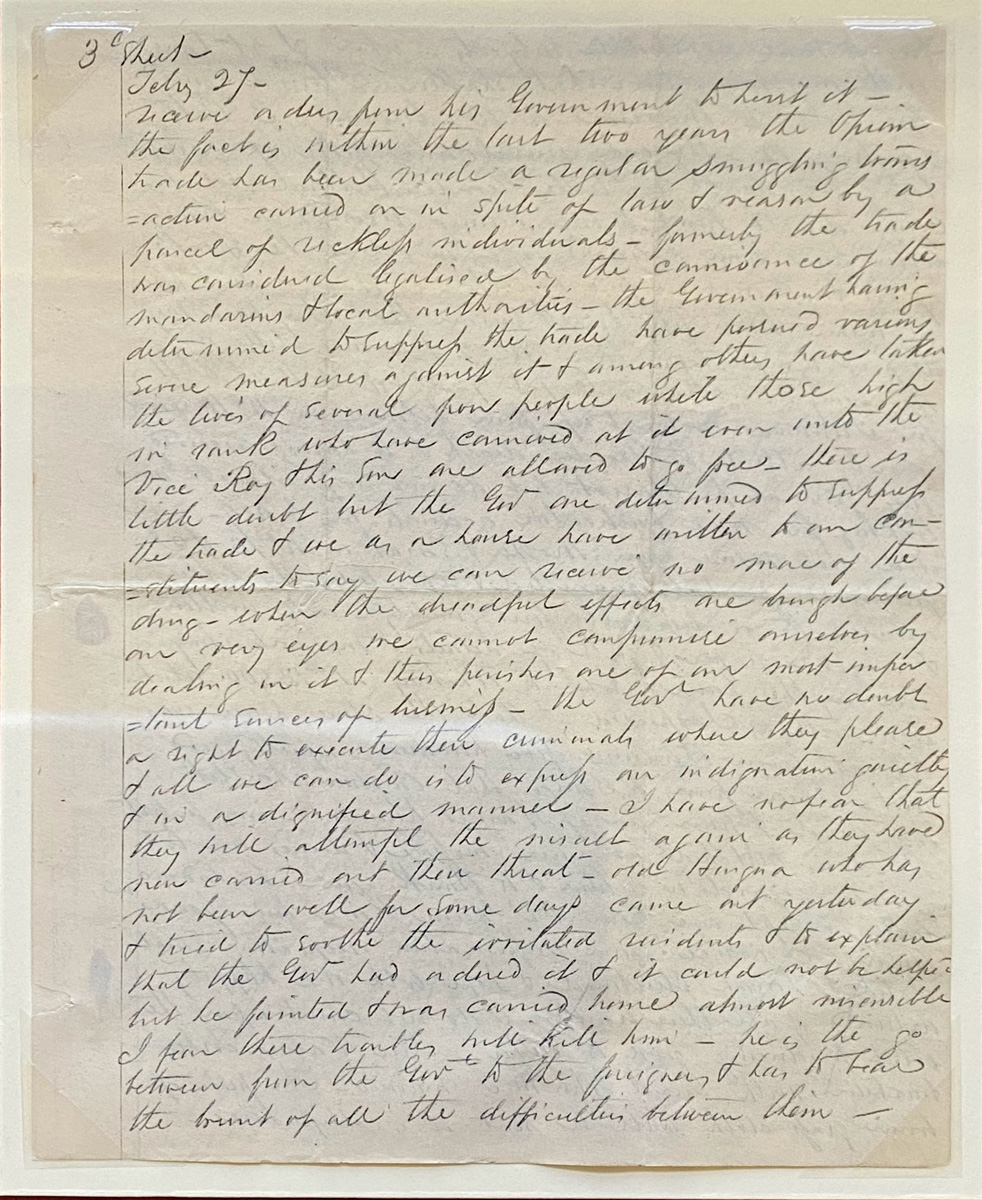

According to Robert Bennet Forbes, in a letter to his wife Rose, dated Feb. 27, 1837:

“I considered it right to follow the example of England, the East India Company and the merchants to whom I had always been accustomed to look up to as exponents of all that was honorable in trade.”

How does first learning about the harmful effects of the opium trade impact (or not impact) how you read the biographies of Forbes family members and see their portraits?

The Forbes family members worked for various family-owned and related companies, including Perkins & Co. and Russell & Co, which acquired Perkins & Co. in 1827 and eventually became the largest American Trading firm. Each company conducted robust trade in China.

Rose and Ben

Rose Forbes eagerly awaited news from her husband, Ben, who traveled the world for decades for business. Ben and Rose corresponded throughout his years abroad but letters from China could take months to be delivered to their recipients. Although there are no existing letters from Rose to Ben, letters from Ben describe his travel experiences, business practices, and evolving thoughts on opium.

In one letter, Captain Forbes presented a common justification for American opium sales to China:

As to the effect on the people, there can be no doubt it was demoralizing to a certain extent not more so than the ardent use of spirits; indeed it has been asserted…that the…twelve to fifteen pounds of opium-distributed among three hundred and fifty millions of people had a much less deleterious effect on the whole countryside than the vile liquor made of rice called “samshue.”

For the women left at home, correspondence was a critical connection to the Forbes men who traveled to and worked in China, often for years at a time.

Ben kept this small box with correspondence between Thomas and his mother, Margaret, as a memento of his brother.

As Ben returned to Canton in 1838, a decade after his brother Thomas was swept into the Pearl River in a typhoon, he confessed to his wife Rose in Boston:

“I can not help feeling a little dull though the long years have elapsed since that fatal gale. Ten years ago today or yesterday perhaps, the remains of that Brother were deposited in their present home. That when he died we were just beginning to feel like Brothers, has always been a source of great uneasiness to me.”

Chinese Exports & Forbes Family Wealth

Unknown Chinese Maker, 19th century

Chinese export porcelain

FHM 1987.6.007 a,b

Gift of the Heirs of Mrs. Weston Howland

The China Trade enriched American businesses with capital and American homes with luxury. It was not just merchants pursuing profit, but consumers at home creating massive demand for tea and other products from around the world. People who bought delicious tea, spices, beautiful ceramics or silk, also supported the China Trade.

Symbols of Wealth

By the time the Forbeses were trading in China, there was already a robust global economy built around quality Asian products for the international market. Chinese exports for the American market sparked trade between the nations and transformed tastes in the U.S.

Chinese porcelain was considered the finest in the world — that is why porcelain is sometimes simply called “china.” China exported a wide variety of fine-quality porcelain, as well as silver and less expensive ceramics.

Chinese porcelain was often made specifically for the European and American markets. This bowl is decorated with symbols of the Forbes family in Scotland, including thistles, the national flower.

Forbes Family bowl

Unknown Chinese Maker, c. 1780

Chinese export porcelain

FHM 1976.037

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Alex C. Forbes

A favorite of Ben Forbes, this rare pattern of Chinese porcelain depicts bats and lotus flowers on a deep blue ground, accented with auspicious shou characters – symbols of longevity. This design reflects the wealthy Chinese taste that Ben experienced in the home of high-ranking hong merchants, like Hou Qua. This was one of the many dinner services he brought back from China.

Blue Lotus and Bat dish service

Unknown Chinese Maker, 19th century

Porcelain with overglaze enamels

FHM 1965.1.481 – 486, .488, .489, .492, .494-.498, .501-.503

Gift of H.A. Crosby Forbes

Robert Bennet Forbes won this silver coffeepot in a sailing regatta on the Pearl River. He sent it home to Rose, who wrote back, “I cannot tell you how charmed I was with the Coffee Pot – I think it is without exception the handsomest present I ever received…the shape is beautiful and the chased work elegant…”

As Rose clearly appreciated, this coffeepot is a beautiful early example of Chinese Export Silver. For many years, the existence of Chinese silver was questioned, as many such pieces were mistakenly identified as Georgian or Victorian. This particular piece, and its supporting documentation in the form of letters between Ben and Rose, contributed to the establishment of Chinese Export Silver as a field for scholarly and scientific research. It also contributed to a greater understanding and appreciation of Chinese Export art as whole.

Coffee pot

Wongshing, 1838

Silver

FHM2022.003

Gift of Robert P. Forbes and Douglas Forbes

Consider these objects’ visual presentation: traditional Chinese iconography, demonstration of great skill and craftsmanship, and reformulation for Western markets. How are the objects and their visuality complicated by how the Forbes family acquired them?

Commissioner Lin ZeXu, the “Century of Humiliation,” and Ethnocentrism in the China Trade

Century of Humiliation

Modern China grew out of 19th-century trade with Western merchants like the Forbeses. With the onset of the First and Second Opium Wars (1839-43 and 1856-60), the rapid and extensive damage done to the Chinese economy weakened imperial powers and laid the foundations for its continued resentment of the West. This “Century of Humiliation”—as it is taught in Chinese schools—underlies many of China’s diplomatic and trade policies today, revealing deep distrust of capitalism and colonialism throughout the world.

How does labeling historical periods aid in understanding?

How is understanding limited?

The ethnocentrism practiced by Chinese officials and American travelers fostered racist stereotypes and “othering” that prevented true cultural exchange and understanding. Consequently the growth of the China Trade was accompanied by exploitation that depended on keeping foreigners and Chinese separated. Chinese and American merchants gained wealth even as they ignored the harm that the opium trade caused. The scale of the trade and the reach of opium into Chinese society meant nearly all Chinese were affected directly or indirectly—and the effects are still felt today.

How are economic systems reliant on and shaped by systems of racialization?

Key Figures in China

Hou Qua

As one of the wealthiest men in the world, Houqua’s stunning gardens were widely known and admired – he gave RBF and JMF (and other high-ranking Western merchants) rare access to Canton beyond its walls, frequently inviting them to his house for dinner. His expansive property was filled with ponds, stone-paths, bamboo, peacocks, standing rocks and rockworks, a promenade, potted flowers, dwarf trees, fruit trees, a river, and more.

The Dao Guang Emperor (1782-1850)

The Emperor at the time the Forbeses were trading in China was the Daoguang Emperor (Reign 1820–50), an ineffective leader facing a rough economic period. The government needed tax money to address neglected infrastructure, including dredging the Grand Canal that would allow better, regulated trade to inland China. Without canal access, trade occurred more along the coast, which encouraged more smuggling. The Emperor was an opium addict, as were most of his court. By the 1830s, up to 20 percent of central government officials, 30 percent of local officials, and 30 percent of low-level officials regularly consumed opium. Following the death of his own son from opium addiction, the Emperor appointed Commissioner Lin to eradicate opium from China.

Commissioner Lin Zexu

Commissioner Lin Zexu, courtname Yuanfu, was a Chinese government official who was regarded as a hero at the time for his role in attempting to rid China of opium. Seen as completely incorruptible, Commissioner Lin led the Qing dynasty’s hardline anti-drug policies meant to combat the influx of opium by Western smugglers. In 1839, he wrote an open letter to Queen Victoria, asking her to cut off the flow of opium to China by British merchants, asking “Have they no conscience?”

As part of his attempt to eradicate opium production, trade, and use in China, Commissioner Lin Zexu orchestrated the seizure and destruction of all opium aboard ships in Canton Harbor. He forced foreign merchants, or “the Barbarians of every nation” as he called them in his proclamation, to deliver “every particle of opium” to him, amounting to nearly 1.2 million kg (2.6 million pounds), valued at $40M (approximately $1B in today’s dollars). Beginning June 3, 1839, 500 workers worked for 23 days to destroy it all, mixing the opium with lime and salt and then tossing it into the Pearl River.

How does this event compare to the Boston Tea Party of 1773?

Philanthropy and Lasting Effects of the Opium Trade

Examining Philanthropy

Historians estimate that 90 million Chinese people (33% of the population at the time) became addicted to opium as the result of the 19th-century opium trade. The Forbeses participated in, orchestrated, and profited from that trade.

And yet, the Forbes family, like other Boston Brahmin families that became wealthy as the result of the China and opium trades, were major philanthropists in Boston and beyond. The trade helped build the American economy by providing the capital for growth of American industry and infrastructure. Those profits were re-invested in railroads, schools, hospitals and other ventures, by the Forbeses and many other Boston merchants.

What legacy did this leave for future generations?

Benefactors of the 19th century largely supported civic projects and supplied aid to poorer relations and friends – projects and people they knew. The impact of their aid was visible to them.

Capt. Forbes raised money to establish Sailors’ Snug Harbor, a home for retired sailors, and served as its first president. He promoted the establishment of swimming schools for children – everyone should know how to swim.

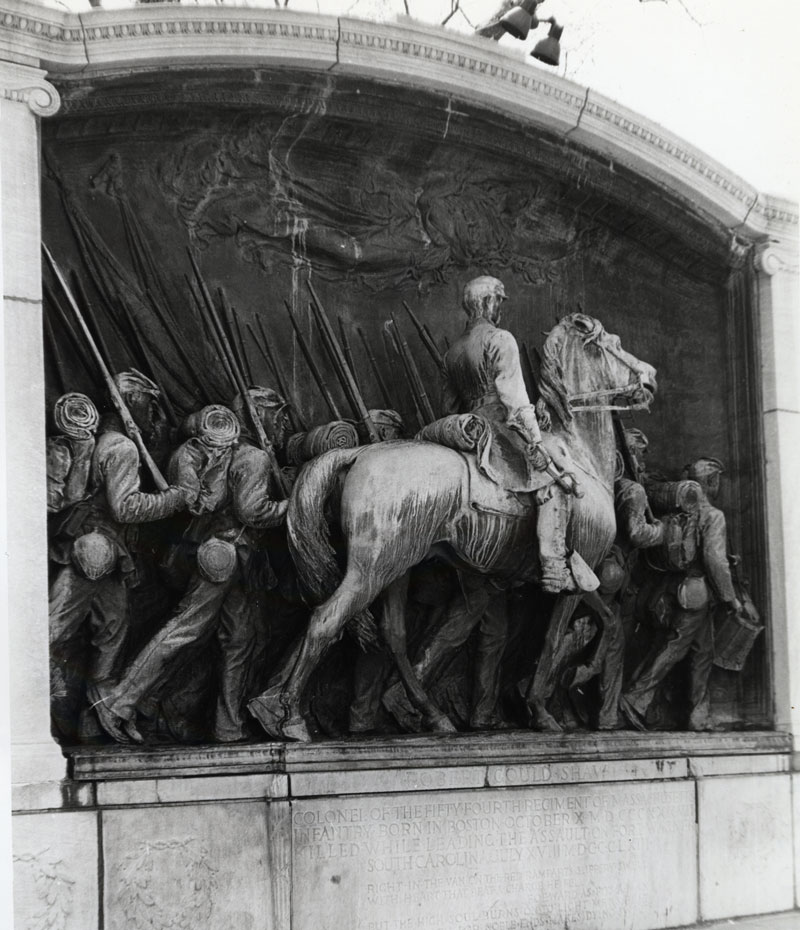

John Murray provided funding for New Englanders who went to fight slavery in Kansas, and he outfitted the 54th Regiment of Colored Troops during the Civil War. Both Ben and John were known to provide aid to widows, children and orphans.

Even today, most philanthropists provide funding that fuels their special interests or causes and benefits certain segments of the population.

How might these issues be addressed in this age of diversity, equity and inclusion?

One of the most remarkable aid efforts in US history was led by the two Forbes brothers and members of the New England Relief Committee in 1847. John Murray Forbes secured the USS Jamestown, a temporarily decommissioned US Navy ship, and Robert Bennet Forbes was named captain for what was the first international humanitarian relief effort, delivering 800 tons of provisions to Cork at the height of the Great Hunger. He even stayed several days to work with Father Theobald Mathew, an Irish leader and champion of the starving Irish, to ensure that the supplies were distributed where they were most needed.

As the Forbeses and other families garnered awards, praise and acclaim from this effort to feed the Irish, there were no known efforts to provide medical aid, solace or even public recognition of the harm caused by the opium trade. China’s society and its economy were devastated, its imperial government completely undermined.

Would Brahmin families providing aid to the Chinese have amounted to admitting guilt or acknowledging responsibility for the harm caused?

The Captain's Shifting Views

Ben Forbes shifted his view of opium smuggling over the course of his life. On October 1, 1839, as he prepared to return to China to make another laq (the amount of money Boston traders believed was needed to lead a comfortable life: $100,000) he wrote to Rose, saying, “Perhaps Providence took away my fortune because I made it in Opium. What I make this time will be free from that stain.”

And in 1882, in his Personal Reminiscences, he wrote, “. . .that the only inscription I desire to have on my gravestone is HE TRIED TO DO HIS DUTY.”